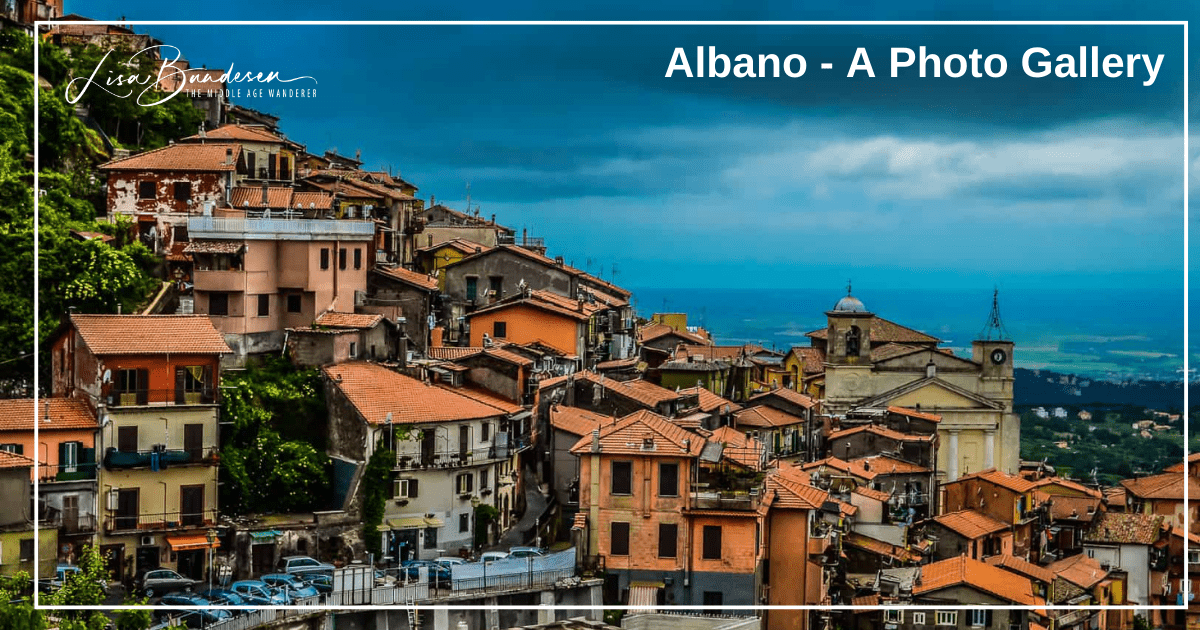

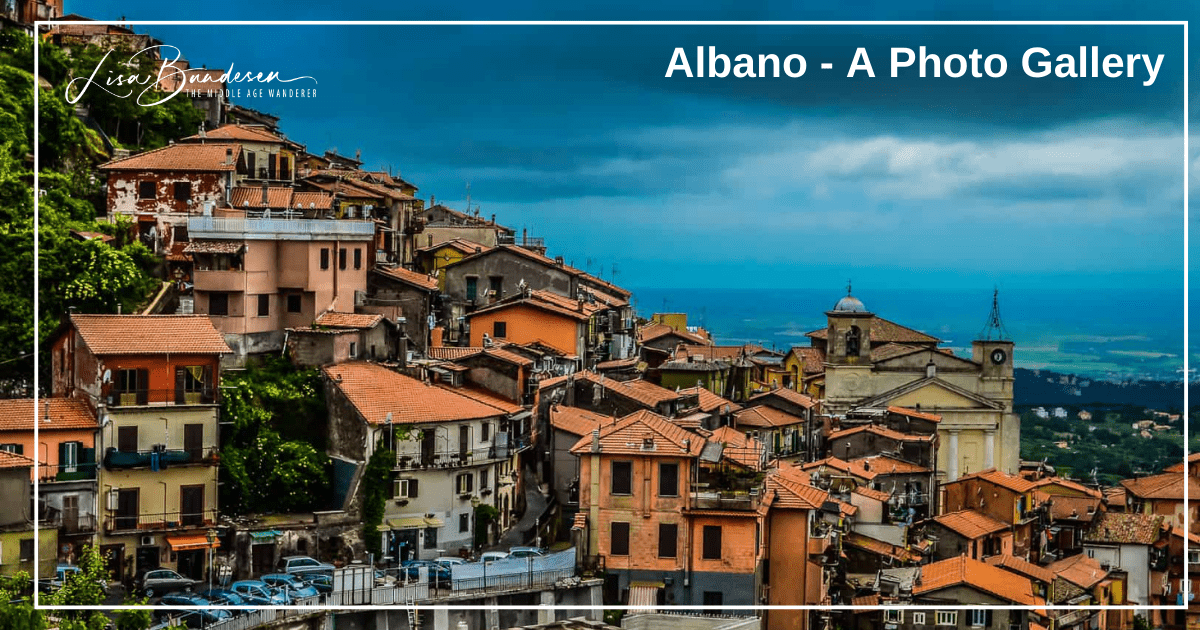

Albano, Italy – A Photo Gallery

Albano is a beautiful town and great place to spend time wandering the streets, exploring and sampling the food from the local shops.

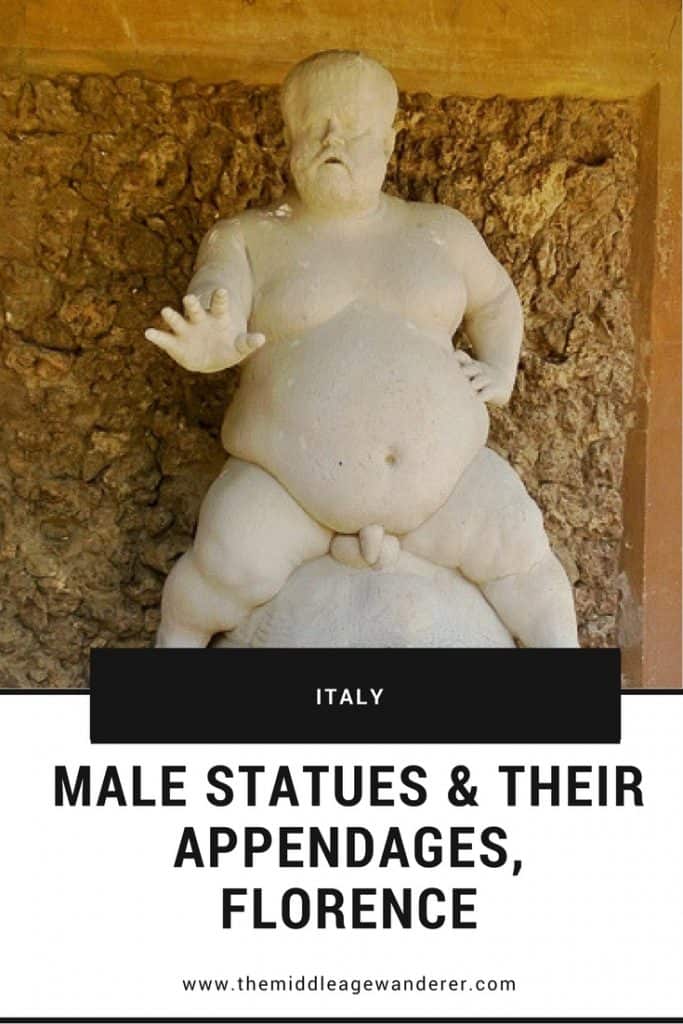

Male statues can be found throughout many countries. But, after reading a rather interesting article about male statues, titled “Why Aren’t Classical Statues Very Well Endowed”, it had me looking back through my photos of my trip to Florence, Italy. The article, in part sets out:

“As it turns out, a lot has changed over the last few thousand years, including how we thing about penis size. Elen Oredsson of the blog How to Talk About Art History explains in one post that ‘cultural values about male beauty were completely different back then. Today, big penises are seen as valuable and manly, but back then, most evidence points to the fact that small penises were considered better than big ones’.”

So, of course, after reading that, I just had to share some of the male statue photos with you, just so you can make up your own mind. I know you want to see them!

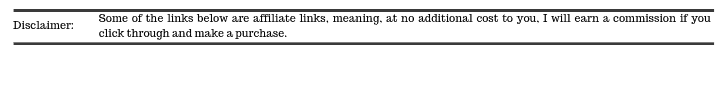

Now obviously, the Statue of David is not in these photos as you can’t take photos in the museum.

The Boboli Gardens are more than just a garden. They are an open air museum show casing centuries old oak trees, fountains and of course sculptures. The gardens are 400 years in the making, starting in the 15th century before being completed in the 19th century.

The Piazza della Signoria has been the centre of political life in Florence since the 14th century. The Palazzo Vecchio Museum and Tower overlook the square. The sculptures in Piazza della Signoria are full of political and contradictory connotations.

The replica Statue of David was placed outside the Palazzo Vecchio as a symbol of the Republic’s defiance of the tyrannical Medici. In contrast the Hercules and Cacus statue was taken by the Medici to show their physical power after their return from exile.

Loggia dei Lanzi is an open air museum next to the Piazza del Signoria.

So after inspecting a number of classical male statues …… well I’ll leave it for you to decide!

Albano is a beautiful town and great place to spend time wandering the streets, exploring and sampling the food from the local shops.

Pompeii, the Roman town, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD is home to brothels and the images that adorned their walls.

A visit to Rome isn’t complete without a visit to the Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, an ancient Roman bath converted into a church.

Have you ever wondered if all classical male statues aren’t very well endowed? You can check for yourself with these from Florence, Italy.

© 2024 The Middle Age Wanderer

Made with

18 Responses

So many appendages and so little time to see them all – this is a quite a series and I haven’t even perused your French appendage collection! Isn’t it interesting that we went from the celebration of the nude figure to the prim and proper Victorian era where that kind overt depiction was frowned upon.

So true Jay. The Victorian era was so prim and proper yet we have statues like these.

Had a great laugh at this! I’ve actually got a photo of the statue of David plus his appendage – taken long ago. I’m sure we were allowed to take photos then, but I’m sure it has changed.

So glad you enjoyed it Alma. Actually there are so many photos of the Statue of David – not sure how strict they are on the policy.

LOL I’ve always wondered this myself, my curiosity is now satisfied but it does make me wonder with regards to “men in power” how many could be adequately represented by the small penis statues?

Haha Faith. So glad you enjoyed the post and yes totally agree with your comment!

Well your front picture certainly got my attention and then held it LOL. Italy is certainly a good place for these sort of statues that mesmerise and entertain in equal measure. A fun piece.

Haha Karen. Glad it got your attention! And Italy is definitely a great place for statue spotting!

Haha sush a funny post, I love it! 😀

I think there was an artexibit in Madrid a few years ago, at one of the biggest galleries, that had a show with a lot of … appendage 😀

Glad you enjoyed it Ann :-).

That certainly got my attention! I’ve worked in the fitness industry for over a decade and even in just that short (comparative) time it’s been interesting to see how what is considered “attractive” has changed. Can’t say it’s been the most positive thing, but it is interesting to see aspects of vanity has changed over the ages as well as the decades!

So true Gabby. It’s definitely interesting to see how vanity has changed.

Such an interesting post and actually something I had never considered before LOL.

Haha now you know all about it Joanne!

What a fun post! I remember many of these sculptures from my visit, but didn’t realize quite how large a collection there is in Florence!

There are definitely lots of male statues in Florence Vasu!

This article made me laugh, in part remembering my first view of David. I was about seven and my sister was about four. My Dad snapped a pic of us looking up at his, um, appendage, with VERY wide eyes. LOL!

Haha that would be a fun photo to look back on.